2 Framework

This study is framed in terms of professional learning networks (PLNs). For this study, I define a PLN as a support system of interconnected tools, resources, people, and spaces — spanning local and online contexts — with the teacher at the center. A PLN frame centers early career teachers’ efforts to establish support systems around themselves, conceptualizing teachers’ support systems in terms of tools, people, and spaces that help improve teaching and learning (Krutka et al., 2017; Trust et al., 2016; Trust & Prestridge, 2021). PLNs emphasize the interconnected, or networked, nature of a support system, with the teacher at the center. PLNs have roots in situated learning theories, which assert that learning occurs within specific contexts (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Putnam & Borko, 2000). Lave and Wenger (1991) described learning as an apprenticeship, a process wherein a newcomer becomes a member of a community of practice. This view of learning-as-situated foregrounds the individual learner; for PLNs, this means focusing on a single teacher who connects to tools, people, and spaces to support and improve their ongoing professional learning. The tools shared in PLNs are useful for teachers’ professional learning and may include knowledge, skills, teaching resources, curricular materials, and encouragement. These tools are shared by people, both individuals and groups, with whom an early career teacher can connect through various spaces (e.g., school of employment, district workshops, social media platforms). Teachers’ willingness to voluntarily construct PLNs in addition to required professional development suggests that there are underlying reasons that justify spending extra time and effort beyond the regular demands of the teaching profession. In sum, a PLN can be understood in terms of why (i.e., underlying reasons) a teacher constructs a support system, what they are looking for (i.e., tools for professional learning), from whom (i.e., people), and where (i.e., spaces).

A PLN frame is well-suited for this study because it foregrounds teachers’ professional learning while expanding the scope of tools and people to potentially include those accessed through emergent spaces like social media. PLNs include elements of traditional professional development in addition to informal learning possibilities (Krutka et al., 2017; Prestridge, 2019; Trust et al., 2016), spanning local and global spaces (Trust et al., 2016). The mix of face-to-face, online, formal, and informal elements highlighted by a PLN framework has the potential to address the gap between research on teacher induction and research on teachers’ use of social media.

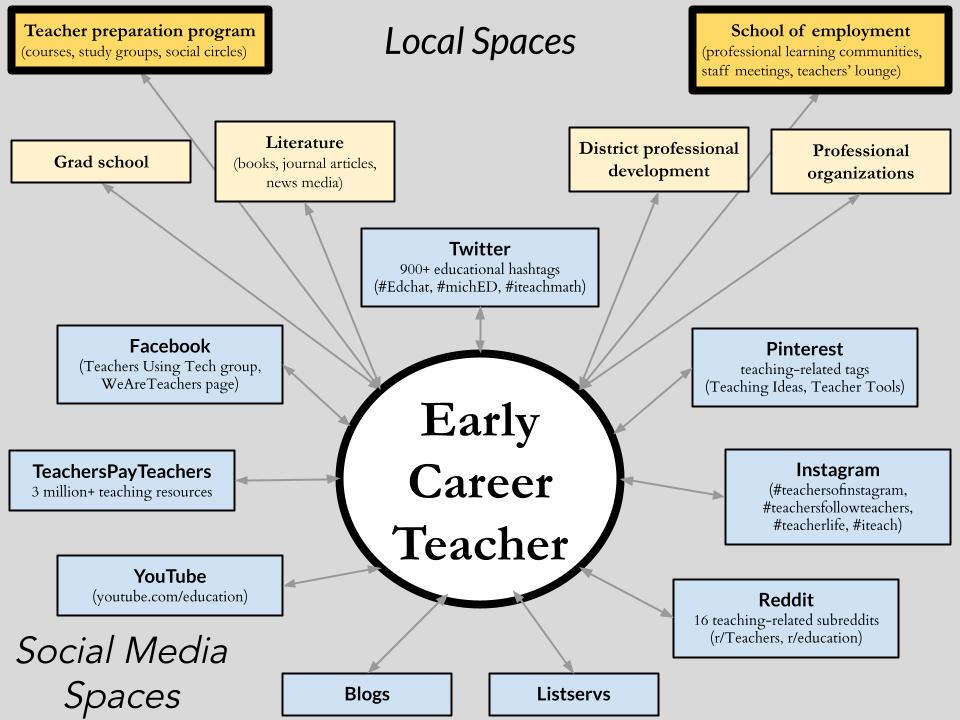

Two other frameworks intersect with the PLN concept and offer additional insight: learning ecology and agency. First, the many spaces comprising an early career teacher’s PLN can be understood as a learning ecology: “the set of contexts found in physical or virtual spaces that provide opportunities for learning” (Barron, 2006, p. 195). In other words, a learning ecology emphasizes the spatial component of a PLN, highlighting that PLNs are composed of interconnected and mutually influential spaces, with the individual teacher at the center (Figure 1). Disparate pieces of a PLN fit together to make a whole (Barron, 2006; Stevenson et al., 2019; Veletsianos et al., 2019) and may change over time (Carpenter et al., 2021; Veletsianos et al., 2019). For instance, an early career teacher may start asking teaching-related questions in the r/Teachers subreddit and learn about policy issues in the r/education subreddit (Staudt Willet & Carpenter, 2021) to complement a recent district professional development workshop discussing new expectations for teaching to standards. In cases like this, participating in informal contexts can support and influence learning in formal contexts (Peters & Romero, 2019).

Figure 1. Spaces for Early Career Teachers’ Professional Learning

Second, early career teachers enact agency when making choices about constructing PLNs. Because of the emphasis on professional learning, an agentic perspective on PLNs specifically highlights teachers’ identity-agency. Identity-agency can be understood as taking responsibility for and actively investing in one’s own self-development as a teacher (Ruohotie-Lyhty & Moate, 2016). This definition is similar to Bandura’s (2001) conceptualization of agency: “to play a part in their self-development, adaptation, and self-renewal with changing times” (p. 2). Identity-agency emphasizes the teacher as an active agent (Tao & Gao, 2017) taking intentional and purposeful actions (Pearce & Morrison, 2011). These agentic actions follow a path starting with recognizing a challenge, forming a strategy to overcome that challenge, and then implementing the strategy (Bandura, 2001). Developing agency is thus a process that takes time and is reinforced by outcomes that are perceived to be positive, whether benefiting students or the teacher (Bartell et al., 2019).

Early career teachers are still actively constructing their professional identities (Juutilainen et al., 2018) in a process where identity development is intertwined with agentic choices and actions (Tao & Gao, 2017). This process of enacting identity-agency includes teachers making their own choices about how to construct a support system from the subset of all tools, people, and spaces available to them (i.e., why they access some contexts but not others). These agentic actions are “influenced by experiences, beliefs, values, and goals in conjunction with the context” (Wray & Richmond, 2018, p. 3). For instance, if an early career teacher had difficulty contextualizing the content of a district professional development workshop, it would be up to them to talk to colleagues in the teachers’ lounge, ask a mentor teacher, or see what answers they could find through social media. The result is a PLN that is “uniquely cultivated” (Trust & Prestridge, 2021, p. 1) to meet the induction needs of each teacher.

In sum, this study considers early career teachers’ construction of support systems with a PLN frame, taking into account ecological and agentic perspectives. Social media have greatly increased access to potential tools, people, and spaces that might help early career teachers navigate induction challenges. An ecological perspective spotlights the relationship between various PLN components, and an agentic perspective draws attention to early career teachers’ intentionality in choosing some components to add to their PLN, but not others.